9 key findings from the landmark Toronto police report on systemic anti-Black discrimination

Toronto police have released a massive new report on how officers use force and strip searches interacting with the city’s racialized communities.That data, collected in 2020 and released publicly Wednesday, shows that Black and other minority populations are more likely to have force used against them — including having firearms pointed at them — and to be subjected to strip searches even after the force changed its policy to reduce the frequent use of that invasive tactic.The results are so stark that police warned officers this weekend to brace for a “challenging” public reaction that will “lead some people to question the hard work you do every day.” And Chief James Ramer apologized “unreservedly” to Black and other racialized Torontonians, coinciding with the release of a 119-slide presentation on the force’s findings.Sam Tecle, assistant professor of sociology at Toronto Metropolitan University noted Toronto police were legislatively forced to release the data after years of protest.“All this data that they’re collecting comes out of community struggle,” he said, adding that the numbers reflect what the Black community already knew.“Can we trust the police to value our lives in these interactions? The data keeps telling us, no.”Here are nine key findings from the new statistics:Black people were almost four times more likely to face police force than their share of the population; five times more likely than white people.Black people were the most disproportionately affected group. Of all use of force incidents, 39 per cent involved a Black person. That’s compared to the Black share of the city’s population of 10 per cent.That discrepancy is even starker than the main comparison used in the police report itself, which compares those who were subject to force to the total number who had encounters with the police — not the total population. That comparison does not account for the Black population being over-policed in the first place; that 10 per cent share of Black people was involved in 24 per cent of police “enforcement actions.”By comparison, white people made up 46 per cent of the population but 36 per cent of use of force reports — far less than their population share.Black people were more than twice as likely as white people to have a firearm pulled on them when the officer believed they were unarmed.The police data also looked at the likelihood of different groups having a firearm pointed at them, and found being Black made it much more likely. In incidents involving force where an officer thought there was a weapon, Black people had a firearm pointed at them 48 per cent of the time, compared to 33 per cent for white people. That disparity only grew in cases where officers didn’t think the alleged suspect was armed. Officers pointed their guns at Black people 2.3 times more often than white people — in 18 per cent of all use of force incidents, compared to 8 per cent for white people. Black and Indigenous people in crisis were nearly twice as likely to have force used on them.The data also zoomed in on how force was used during different types of calls, like those for reported violence and others where a person is believed to be in crisis — incidents that have often drawn criticism for use of force. Compared to the 2020 average for all calls for a “person in crisis,” Black people were 1.9 times more likely to have force used on them. Indigenous people faced force 1.4 times more often. In comparison, white people experienced force 20 per cent less often than the average for all crisis calls.Minority populations were more likely to be subject to force in areas with smaller minority populations.The data looked at use-of-force incidents by group in comparison with the demographic make-up of each of the city’s 17 police divisions and found divisions where a disproportionate number of Black, South Asian, Latino and East/Southeast Asian had force used on them also had smaller populations of those groups.Meaning: The whiter a police division, the more likely it was that minority groups faced disproportionate police force. Officers pointed their firearms in more than a third of all incidents involving force.Having a firearm pointed, discharged or lethally fired is considered the most severe use of force by a police officer. According to the data, officers reported using any type of force 949 times in 2020. Of those incidents, a firearm was pointed at someone in 371 cases, or 39 per cent of all use of force incidents. It was rare that a firearm was actually fired — just four times in 2020; an officer killed someone with their firearm twice. Notisha Massaquoi, assistant professor with the department of health and society at the University of Toronto Scarborough, said that while the frequency of firearms being pointed is itself disturbing, she is more concerned about the lethality of those incidents, pointing to a Ontario Human Rights Commission study published in 2020 that found a Black person was 20 ti

Toronto police have released a massive new report on how officers use force and strip searches interacting with the city’s racialized communities.

That data, collected in 2020 and released publicly Wednesday, shows that Black and other minority populations are more likely to have force used against them — including having firearms pointed at them — and to be subjected to strip searches even after the force changed its policy to reduce the frequent use of that invasive tactic.

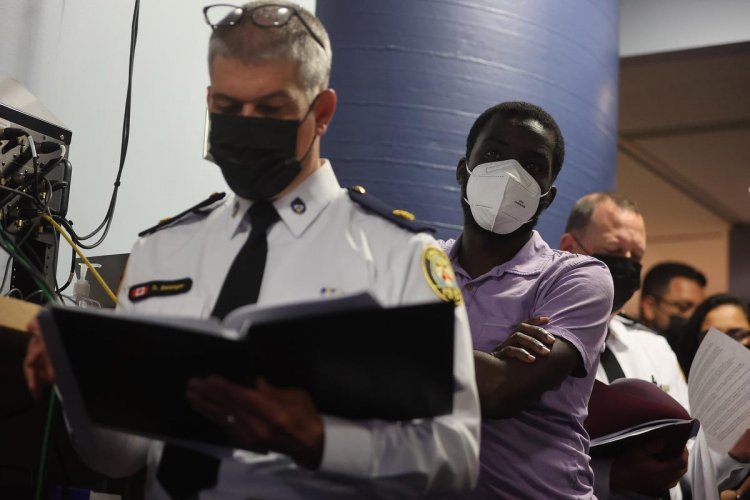

The results are so stark that police warned officers this weekend to brace for a “challenging” public reaction that will “lead some people to question the hard work you do every day.” And Chief James Ramer apologized “unreservedly” to Black and other racialized Torontonians, coinciding with the release of a 119-slide presentation on the force’s findings.

Sam Tecle, assistant professor of sociology at Toronto Metropolitan University noted Toronto police were legislatively forced to release the data after years of protest.

“All this data that they’re collecting comes out of community struggle,” he said, adding that the numbers reflect what the Black community already knew.

“Can we trust the police to value our lives in these interactions? The data keeps telling us, no.”

Here are nine key findings from the new statistics:

Black people were almost four times more likely to face police force than their share of the population; five times more likely than white people.

Black people were the most disproportionately affected group. Of all use of force incidents, 39 per cent involved a Black person. That’s compared to the Black share of the city’s population of 10 per cent.

That discrepancy is even starker than the main comparison used in the police report itself, which compares those who were subject to force to the total number who had encounters with the police — not the total population.

That comparison does not account for the Black population being over-policed in the first place; that 10 per cent share of Black people was involved in 24 per cent of police “enforcement actions.”

By comparison, white people made up 46 per cent of the population but 36 per cent of use of force reports — far less than their population share.

Black people were more than twice as likely as white people to have a firearm pulled on them when the officer believed they were unarmed.

The police data also looked at the likelihood of different groups having a firearm pointed at them, and found being Black made it much more likely.

In incidents involving force where an officer thought there was a weapon, Black people had a firearm pointed at them 48 per cent of the time, compared to 33 per cent for white people.

That disparity only grew in cases where officers didn’t think the alleged suspect was armed. Officers pointed their guns at Black people 2.3 times more often than white people — in 18 per cent of all use of force incidents, compared to 8 per cent for white people.

Black and Indigenous people in crisis were nearly twice as likely to have force used on them.

The data also zoomed in on how force was used during different types of calls, like those for reported violence and others where a person is believed to be in crisis — incidents that have often drawn criticism for use of force.

Compared to the 2020 average for all calls for a “person in crisis,” Black people were 1.9 times more likely to have force used on them. Indigenous people faced force 1.4 times more often.

In comparison, white people experienced force 20 per cent less often than the average for all crisis calls.

Minority populations were more likely to be subject to force in areas with smaller minority populations.

The data looked at use-of-force incidents by group in comparison with the demographic make-up of each of the city’s 17 police divisions and found divisions where a disproportionate number of Black, South Asian, Latino and East/Southeast Asian had force used on them also had smaller populations of those groups.

Meaning: The whiter a police division, the more likely it was that minority groups faced disproportionate police force.

Officers pointed their firearms in more than a third of all incidents involving force.

Having a firearm pointed, discharged or lethally fired is considered the most severe use of force by a police officer. According to the data, officers reported using any type of force 949 times in 2020. Of those incidents, a firearm was pointed at someone in 371 cases, or 39 per cent of all use of force incidents.

It was rare that a firearm was actually fired — just four times in 2020; an officer killed someone with their firearm twice.

Notisha Massaquoi, assistant professor with the department of health and society at the University of Toronto Scarborough, said that while the frequency of firearms being pointed is itself disturbing, she is more concerned about the lethality of those incidents, pointing to a Ontario Human Rights Commission study published in 2020 that found a Black person was 20 times more likely than a white person to be fatally shot by police between 2013 and 2017.

She noted, an officer can’t kill someone unless their gun is pointed.

Latino and East/Southeast Asians were less likely to encounter police, but when they did, they were subject to disproportionate use of force.

Unlike the Black population, both Latino and East/Southeast Asians were underrepresented in encounters with police when compared to their share of the city’s total population.

But, the data found, when those groups did come in contact with police, they were overrepresented in officers’ use of force — what police called “low contact, high conflict.”

These racial disparities found cannot be explained by other data.

Importantly, the police data looked at geographic and other ways of analyzing the data, but it did not change the fact that Black and other minority group were still overrepresented — evidence against the idea that some other factor explains away the finding of anti-Black bias.

For example, Black people were similarly likely to be subjected to force more often regardless of whether they had several recent encounters with police or just one.

Nearly a third of all Indigenous people who were arrested were strip-searched.

The Indigenous population was most disproportionately represented in the strip search data released by police. In total, 28.6 per cent of all Indigenous people arrested in 2020 were strip-searched, compared to 22 per cent of all people arrested. (Those numbers include the months after October of that year when police leadership made changes to strip search policy, reducing the overall number of searches.)

Regardless of race, those arrested downtown were far more likely to be strip-searched.

Map-based data for Black, Indigenous and white populations show a high rate of strip-searching in several downtown police divisions — 14, 51 and 52 — well above the city-wide totals. In those divisions, strip search rates were between 41 to 70 per cent of all arrests.

That means someone arrested downtown has closer to a one-in-two chance of being strip searched, compared to a one-in-10 or one-in-five chance for those groups in North York’s 33 Division.

Jennifer Pagliaro is a Toronto-based crime reporter for the Star. Follow her on Twitter: @jpags

.jpg?#)